Ewing sarcoma is one of the most common bone cancers seen in children, and if it spreads, it can be deadly. A study headed by researchers at the Institute of Mother and Child, Warsaw, have now found that combining first line therapy for Ewing sarcoma with a drug called pazopanib, which was originally developed for renal cell carcinoma, demonstrated striking success in treating a small group of young patients. 85% of the treated patients survived two years after diagnosis, and there was no disease progression for two-thirds of patients. The team calls for larger studies which can develop this treatment further.

“Survival rates were higher than in historical controls, suggesting it may extend lives and, importantly, do so without adding severe toxicity,” said Anna Raciborska, MD, who is lead author of the team’s published report in Frontiers in Oncology. “Moreover, the quality of life of treated children was good. After the end of IV treatment, patients could receive pazopanib as a home treatment.”

Data from the study are published in a paper titled “Pazopanib in patients with primary multi-metastatic bone Ewing sarcoma.” Raciborska further noted, “While we wait for new treatment options, it is possible to implement this existing drug to improve outcomes in very high-risk patients,” she added. “It opens the door to targeted therapies earlier in the disease course, potentially improving survival and quality of life.”

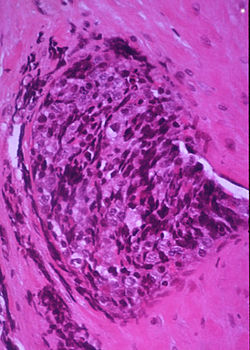

Ewing sarcoma (ES) accounts for about 40% of all bone malignancies in children and young adults, and three percent of soft tissue sarcoma (STS), the authors noted. But while the availability of multimodal therapy has increased survival rates to 70-75% for patients with primary localized bone disease, patients with primary multi-metastatic bone ES disease have what they describe as a “dismal outcome.” The authors continued, “Currently, as the conventional chemotherapy possibilities have been exhausted and the efficiency of the existing treatment procedures are inadequate, more often novel drugs based on alternative mechanisms of action are being sought …”

Pazopanib is a kinase inhibitor that was originally developed for renal cell carcinoma, and approved in 2009 for the treatment advanced/metastatic renal cell carcinoma and STS in adults. The drug is designed to block tumor growth and metastasis by inhibiting angiogenesis. “Its moderate toxicity profile and the promising results observed in a few studies on extraosseous ES allow to consider that pazopanib may also be a reasonable treatment option for heavily pretreated patients with bone ES,” the researchers noted. “Pazopanib is a pill that blocks the tumor’s ability to grow new blood vessels, which tumors need to survive and spread,” said Raciborska. “By cutting off this ‘blood supply’, the drug presumably makes tumors weaker and more sensitive to chemotherapy and radiation. This may slow down the disease and help existing treatments work better.”

To evaluate the drug against ES in young patients, Raciborska and colleagues incorporated pazopanib into the treatment regimens of children with multi-metastatic Ewing sarcoma, in the hope that combining it with other treatments would produce a better result by targeting different aspects of the cancer simultaneously. “Our study is the first one to include very young patients,” the researchers pointed out.

Between 2016 and 2024, 11 young patients received pazopanib alongside standard first-line treatments at the Warsaw Mother and Child Institute. At the time of starting pazopanib, the median age was 14.2 years (range 5.1 to 17.8 years). The success of this additional treatment was tracked as part of their regular care, with imaging and lab tests, and careful monitoring of any possible side-effects. The goal was to determine whether the additional treatment helped control their cancer, and whether any side-effects were manageable.

“All patients received standard first-line treatment, including chemotherapy based on VIDE or VDC/IE regimen, followed by surgery and/or radiation therapy,” the team explained. “The primary tumor was operated on in five patients. Ten patients received concurrent radiation therapy, and three [received] autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.”

The participants took pazopanib during and after their chemotherapy, although treatment was paused for surgery and stopped if the disease progressed or patients experienced unacceptable side effects. On average, the patients took pazopanib for 1.7 years. At the time of study writing, six patients were still taking pazopanib.

Imaging showed that all but one of the patients were clearly responding to treatment. One child’s cancer progressed, two relapsed, and one died—but 10 patients are still alive, with a median time follow-up of 2.6 years (range 1.2 to 9.2 years). Although combining cancer treatments carries a risk of increasing the treatment toxicity, pazopanib was also very well tolerated, with minimal, treatable side-effects. “A high response rate (ten patients, 90.9%) was noted in this population,” the authors wrote, “and toxicity was acceptable. Importantly, according to our knowledge, it is one of the first reported studies using pazopanib in this group of patients.”

The scientists calculated a two-year overall survival rate of 85.7%, while 68.2% of patients made it to the end of the second year without a new ‘event’, meaning their cancer remained stable. This is a better result than a previous study on adult patients, suggesting that pazopanib could be more effective and better tolerated in children, or when given earlier in the treatment course.

However, the researchers stress that much more work needs to be done in larger patient groups to validate these exciting early results. Multi-metastatic Ewing sarcoma is rare, so there are few large-scale randomized clinical trials targeting it. But while new treatments are in development, the researchers encourage the scientific community to test the use of pazopanib as an option to help children with severe metastases further. “Pazopanib turned out to be effective in patients with primary multi-metastatic Ewing sarcoma and particularly could be considered as an option for them. This regimen deserves further investigation,” the authors stated.

“While the results are encouraging, larger controlled trials are needed before changing standard practice,” added Raciborska. “Our study could serve as a basis for creating prospective, multicenter clinical trials to confirm these promising results. However, this requires a lot of work and the commitment of resources. Perhaps future EU programs will allow it. We hope that this will be possible.”

The authors also note the potential to start pazopanib treatment in earlier stage disease, and to combine the drug with other forms of therapy. “Given pazopanib’s anti-angiogenic activity, it is conceivable that its use in earlier disease stages could help suppress the formation of new metastatic sites,” they noted. “Moreover, the potential for combining pazopanib with immunotherapy, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors, is an emerging areas of interest.”