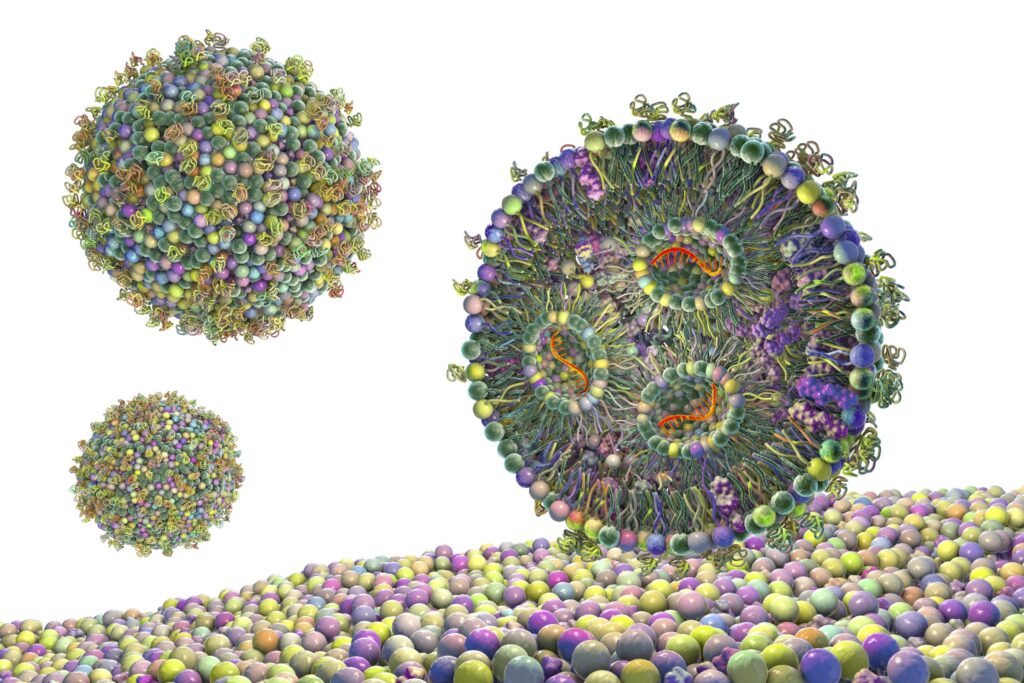

Lipid nanoparticles may deliver better when they are a little disorganized. That’s according to new research from a study led by scientists at the University of Copenhagen that will be presented at the Biophysical Society Annual Meeting which will be held in San Francisco from February 21-25 this year.

Their research focused on lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) which were crucial to the success of mRNA vaccines for Covid-19. Scientists are now using them to deliver treatments for cancer, rare genetic diseases, and other conditions. A persistent challenge is that only a small fraction of the cargo carried by LNPs—about one to five percent—get released inside cells. And “this low efficiency limits what we can do with LNPs as therapeutics,” said Artu Breuer, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in biophysics at the University of Copenhagen. “For example, in cancer treatment where cells are dividing rapidly, if you deliver too little RNA, the cells outpace the therapy.”

Using a new approach that allowed them to examine drug-delivery vehicles in finer-grained detail, the scientists sought to understand why the delivery efficiency varies so much. Specifically Breuer and his colleagues developed a high-throughput method that measures individual nanoparticles—about a million at a time—rather than just looking at the average properties of a batch.

For the study, the scientists used their tool to measure both the size of each particle and how much cargo it contained.“Instead of assuming that every nanoparticle in a batch is the same, we found enormous variation,” Breuer said. “And we discovered two distinct subpopulations: organized particles where the cargo is neatly structured, and amorphous particles where it’s more disorganized. The surprise was that the messy ones actually work better inside cells.”

Drug developers have historically focused on efficiently packing as much medicine as they can into each nanoparticle. Breuer and his colleagues’ findings suggest that highly organized particles may actually resist releasing their cargo once they reach their destinations. Breuer explained it this way. “In an organized nanoparticle, the positively charged lipids are tightly bound to the negatively charged RNA. When the particle enters a cell, even though conditions change, those attractions hold everything together. But in a disorganized particle, there’s some separation between the charges. When conditions change inside the cell, the positive charges repel each other, and the particle falls apart—releasing the medicine.”

The results suggest that it may be better for developers of LNPs to focus on maintaining a disorganized internal structure that lets cargo escape once it enters cells rather than maximizing the quantity of the cargo.

“We’re aiming in the opposite direction of what the field has been pursuing,” Breuer said. “I’m not saying we should have empty nanoparticles, but we need to find ways to load enough RNA while still keeping that disorganized structure that’s more effective inside cells.”