A widely used antidepressant drug could help the immune system fight cancer, according to UCLA research. The newly reported study showed that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) significantly enhanced the ability of T cells to fight cancer and suppressed tumor growth across a range of cancer types in both mouse and human tumor models. The work identified the serotonin transporter (SERT) as a promising immune checkpoint target.

“It turns out SSRIs don’t just make our brains happier; they also make our T cells happier—even while they’re fighting tumors,” said research lead Lili Yang, PhD, a member of the Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at UCLA. “These drugs have been widely and safely used to treat depression for decades, so repurposing them for cancer would be a lot easier than developing an entirely new therapy.”

Yang is senior author of the researchers’ published paper in Cell, titled “Serotonin transporter inhibits antitumor immunity through regulating the intratumoral serotonin axis,” in which they concluded that their findings “… provide fundamental insights into the molecular network governing T cell antitumor immunity and could guide the development of next-generation cancer immunotherapy.”

Immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) is a “potent strategy for cancer immunotherapy,” the authors wrote, and since 2024, 13 ICB antibody therapies have been approved by the FDA for treating solid tumors. These therapies target cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4), programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1), or lymphocyte activation gene 3 (LAG-3). However, the authors continued, despite “remarkable” cases of complete remission in some patients, “… ICB efficacy is limited by individual patient characteristics, as the relevance of specific checkpoints varies across tumor types and individual tumor microenvironments (TME).”

![Dr. Lili Yang [Elena Zhukova/UCLA Broad Stem Cell Research Center]](https://www.genengnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/low-res-5-208x300.jpeg)

ICB treatments only have an effect in about 15–25% of treated patients, and many of these individuals will experience tumor relapse. And while some progress has been made in combining existing ICB treatments to enhance efficacy, the team stated, “… identification of nonredundant immunomodulatory molecules that reshape the TME to better support a potent immune response remains a focus of ongoing cancer immunotherapy research.”

According to the CDC, one out of eight adults in the United States takes an antidepressant, and SSRIs are the most commonly prescribed. These drugs increase levels of serotonin—the brain’s “happiness hormone”—by blocking the activity of the serotonin transporter.

While serotonin is best known for the role it plays in the brain, “only about 5% of the body’s serotonin is synthesized in the brain,” the team noted. Serotonin is, importantly, also a critical player in processes that occur throughout the body, including digestion, metabolism, and immune activity.

Yang and her team first began investigating serotonin’s role in fighting cancer after noticing that immune cells isolated from tumors had higher levels of serotonin-regulating molecules. At first, they focused on MAO-A, an enzyme that breaks down serotonin and other neurotransmitters, including norepinephrine and dopamine.

In 2021, Yang and colleagues reported that T cells produce MAO-A when they recognize tumors, which makes it harder for them to fight cancer. The researchers found that MAO inhibitors (MAOIs) help T cells overcome the immune checkpoint to better fight cancer, and also showed that MAOIs block immunosuppressive tumor-associated macrophages, suggesting that their use could improve cancer immunotherapy. Their combined research demonstrated that treating mice with melanoma and colon cancer using MAOIs—the first class of antidepressant drugs to be invented—helped T cells attack tumors more effectively.

However, because MAOIs have safety concerns, including serious side effects and interactions with certain foods and medications, the team turned its attention to a different serotonin-regulating molecule, SERT.

“Unlike MAO-A, which breaks down multiple neurotransmitters, SERT has one job—to transport serotonin,” explained Bo Li, PhD, first author of the team’ newly reported study and a senior research scientist in the Yang lab. “SERT made for an especially attractive target because the drugs that act on it—SSRIs—are widely used with minimal side effects.”

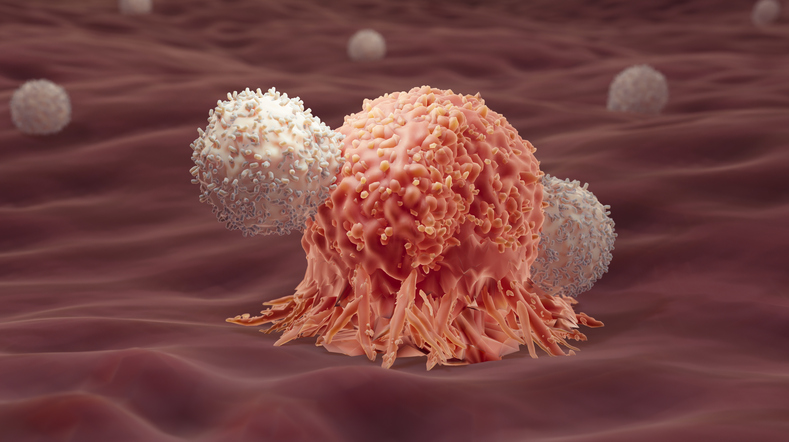

For their work now reported in Cell, the team tested SSRIs in mouse and human tumor models representing melanoma, breast, prostate, colon, and bladder cancer. They found that SSRI treatment reduced average tumor size by over 50% and made the cancer-fighting T cells, known as killer T cells, more effective at killing cancer cells.

“SSRIs made the killer T cells happier in the otherwise oppressive tumor environment by increasing their access to serotonin signals, reinvigorating them to fight and kill cancer cells,” said Yang, who is also a professor of microbiology, immunology, and molecular genetics and a member of the UCLA Health Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center.

“… we identify SERT as an immune checkpoint negatively regulating CD8 T cell antitumor immunity through modulating intratumoral T cell-autocrine serotonin and demonstrate the potential of targeting the intratumoral serotonin axis using SSRI antidepressants for T cell-based cancer immunotherapy,” the investigators further stated.

The team also investigated whether combining SSRIs with existing cancer therapies could improve treatment outcomes. They tested a combination of an SSRI and anti-PD-1 antibody ICB therapy in mouse models of melanoma and colon cancer. ICB therapies work by blocking immune checkpoint molecules that normally suppress immune cell activity, allowing T cells to attack tumors more effectively. The results were striking, and showed that the combination significantly reduced tumor size in all treated mice and even achieved complete remission in some cases.

“Immune checkpoint blockades are effective in fewer than 25% of patients,” said James Elsten-Brown, a graduate student in the Yang lab and co-author of the study. “If a safe, widely available drug like an SSRI could make these therapies more effective, it would be hugely impactful.” In their paper, the team noted, “Our findings provide a rational mechanistic basis for investigating the clinical effects of SSRIs on CD8 T cell antitumor immunity and examining the potential benefits of combining SSRIs with existing ICBs in cancer patients,” the team stated.

To confirm their findings, the researchers will investigate whether real-world cancer patients taking SSRIs have better outcomes, especially those receiving ICB therapies. “Since around 20% of cancer patients take antidepressants—most commonly SSRIs—we see a unique opportunity to explore how these drugs might improve cancer outcomes,” said Yang, who is also a member of the Goodman-Luskin Microbiome Center and the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy. “Our goal is to design a clinical trial to compare treatment outcomes between cancer patients who take these medications and those who do not.”

Yang added that using existing FDA-approved drugs could speed up the process of bringing new cancer treatments to patients, making this research especially promising. “Studies estimate the bench-to-bedside pipeline for new cancer therapies costs an average of $1.5 billion,” she said. “When you compare this to the estimated $300 million cost to repurpose FDA-approved drugs, it’s clear why this approach has so much potential.”

The newly identified therapeutic strategy is covered by a patent application filed by the UCLA Technology Development Group on behalf of the Regents of the University of California, with Yang and Li as co-inventors.