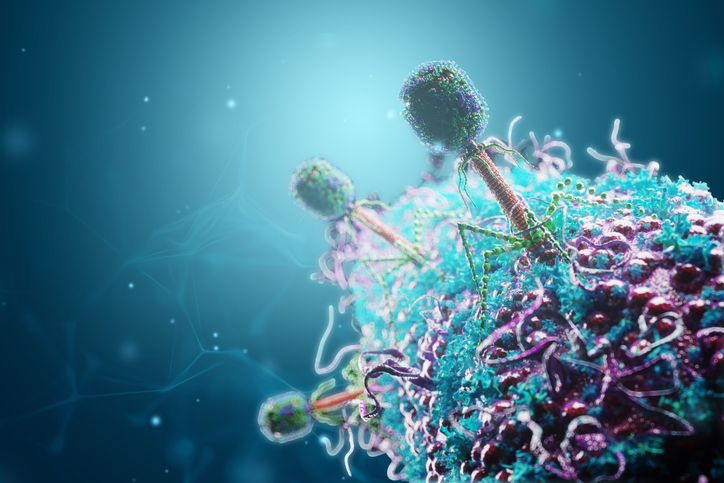

As antibiotic-resistant infections increasingly threaten public health, interest in bacteriophages as therapeutics has seen a resurgence. However, the field remains largely limited to naturally occurring strains, as laborious strain engineering techniques have restricted the pace of discovery and creation of tailored therapeutic strains.

In a new study published in PNAS titled, “A fully synthetic Golden Gate assembly system for engineering a Pseudomonas aeruginosa phiKMV-like phage,” researchers from New England Biolabs (NEB) and Yale University describe a fully synthetic bacteriophage engineering system for P. aeruginosa, a multi-drug resistant bacterium.

Using NEB’s High-Complexity Golden Gate Assembly (HC-GGA) platform, the researchers engineered bacteriophages synthetically using sequence data rather than bacteriophage isolates. The team assembled a P. aeruginosa phage from 28 synthetic fragments engineered with point mutations and gene insertions. New programmed modifications included swapping tail fiber genes to alter the bacterial host range and inserting fluorescent reporters to visualize infection in real time.

“Even in the best of cases, bacteriophage engineering has been extremely labor-intensive. Researchers spent entire careers developing processes to engineer specific model bacteriophages in host bacteria,” said Andy Sikkema, PhD, the study’s co-first author and research scientist at NEB. “This synthetic method offers technological leaps in simplicity, safety and speed, paving the way for biological discoveries and therapeutic development.”

NEB’s Golden Gate Assembly platform removes the reliance on propagation of physical phage isolates and specialized strains of host bacteria, a heightened challenge for therapeutically-relevant phages that specifically infect human pathogens. The process also removes the need for labor‑intensive screening or iterative editing required by in-cell engineering methods.

Unlike DNA assembly methods that join fewer and longer DNA fragments, Golden Gate Assembly’s segments are shorter, which leads to less toxicity to host cells and less probability for errors. The method is also less sensitive to the repeats and extreme GC content found in many phage genomes.

The study was a result of the intersection of expertise between NEB’s scientists, who developed the basic tools to make Golden Gate reliable for large targets and many DNA fragments, and bacteriophage researchers at Yale University who collaborated on new applications.

Researchers at NEB first worked to optimize the method in a model phage, Escherichia coli phage T7. Since then, partnering teams have worked with NEB scientists to expand the method to non-model bacteriophages that target highly antibiotic-resistant pathogens.

A related study uses the Golden Gate method to synthesize high-GC content Mycobacterium phages. Additionally, researchers from Cornell University have worked with NEB to develop a method to synthetically engineer T7 bacteriophages as biosensors capable of detecting E. coli in drinking water.

“My lab builds ‘weird hammers’ and then looks for the right nails,” said Greg Lohman, PhD, senior principal investigator at NEB and co-author on the study. “In this case, the phage therapy community told us, ‘That’s exactly the hammer we’ve been waiting for.’”