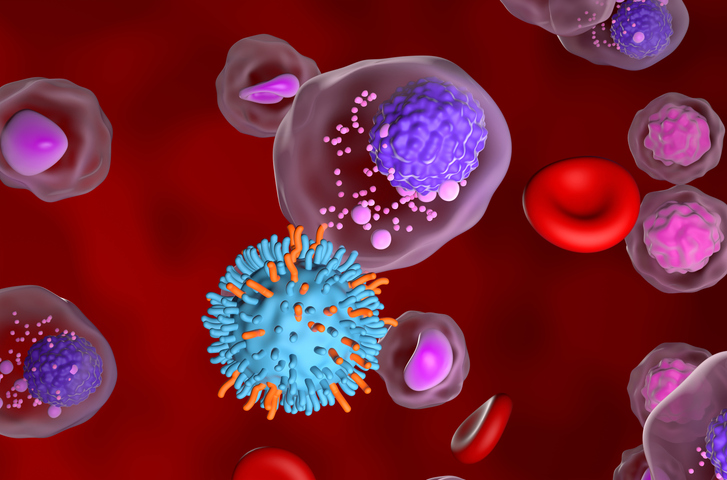

A map of the immune cell landscape found in the bone marrow of patients with multiple myeloma could shed light on how the immune system interacts with cancerous plasma cells. It could also help scientists determine how aggressive a patient’s cancer is likely to be, as well as drive the development of more effective immune-based therapies.

The map is the subject of a new Nature Cancer paper titled “A single-cell atlas characterizes dysregulation of the bone marrow immune microenvironment associated with outcomes in multiple myeloma.” The study was done by a group of scientists from multiple institutions, including Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis (WashU Medicine), Emory School of Medicine, and Harvard Medical School, working in collaboration with the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation (MMRF).

Multiple myeloma is the second most common blood cancer, accounting for about 15–20% of new blood cancer diagnoses in the United States each year, according to one estimate. About 60% of patients are still living five years after diagnosis. Newer treatment options have successfully extended patient survival for up to a decade in some cases. But patients almost always relapse.

“It is time for a better understanding of the immune system in multiple myeloma,” said co-senior author Li Ding, PhD, a professor of medicine and a research member of Siteman Cancer Center based at WashU Medicine and Barnes-Jewish Hospital. “In addition to targeting the cancerous plasma cells directly, we also want new and better ways to activate the immune system to attack the malignant cells. This large-scale immune cell atlas will serve as a critical resource to investigators studying multiple myeloma and working to develop better therapies.”

Some of the newer therapies for multiple myeloma are based on the immune system, including CAR-T cells and bispecific antibodies. But the scientists in the current study believe their map could open a door to other, more effective treatment options. “As immunotherapies like CAR-T cells and bispecific antibodies become central to treatment, understanding the immune context in which they operate is essential,” said Ravi Vij, MD, a co-author on the study and a medical oncologist at WashU Medicine. “Clinically, this work lays the foundation for immune-informed risk stratification and rational development of new therapies that not only target the tumor but also restore effective anti-myeloma immunity.”

The map could also help scientists and clinicians better categorize patients based on the severity of their disease. Current methods for determining whether a patient has high-risk multiple myeloma versus standard risk require combining genetic features of the cancer cells with clinical data from the patients. Adding an immune component could improve how patients are categorized and ultimately what the most optimal treatment options are.

But it will take some time to get there. “More work is needed to develop specific immune-based blood tests, for example, that clinicians could order to better identify the aggressiveness of a particular case of multiple myeloma and help them select the best treatments for that patient,” Ding said. “This immune cell atlas fills a gap in knowledge that is needed to develop these types of new clinical tools.”

To develop the map, the scientists used single-cell RNA sequencing to generate data from almost 1.4 million plasma and immune cells in bone marrow from 337 newly diagnosed cases of multiple myeloma. The patients were part of MMRF’s long-running CoMMpass study of patients with multiple myeloma.

Upon analyzing data from different types of cells, including cytotoxic CD4+ T cells, mast cells, and fibroblasts, the scientists found that patients with certain types of immune cells in their bone marrow at diagnosis were more likely than others to relapse quickly, meaning their cancer returned after a first round of treatment.

The team also reported observing a signaling pattern between cancer cells and immune cells that drives inflammation, which might boost the cancer’s growth in patients with aggressive disease, as well as a type of T cell that suppressed immune activity against cancer instead of attacking it.