Moderna’s efforts to advance its cancer pipeline “make sense” against the backdrop of a more skeptical U.S. government attitude toward infectious disease vaccines, the company’s oncology chief told Fierce.

The mRNA-focused biopharma has firsthand experience of Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s campaign against both vaccines and mRNA after the government ended funding for Moderna’s bird flu vaccine candidate earlier this year. Since then, the HHS has announced a plan to end mRNA vaccine work funded by the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA).

While the political climate for developing infectious disease vaccines looks uncertain, Kyle Holen, M.D., head of development, therapeutics and oncology at Moderna, arrived at the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress in Berlin armed with data from a more promising candidate: mRNA-4359, a cancer drug that encodes PD-L1 and IDO antigens.

When asked by Fierce whether Moderna was deliberately focusing its efforts in oncology, where it is likely to meet less political resistance, Holen pointed out that Moderna was founded as a rare disease and oncology company.

“So that’s always been a part of Moderna’s strategy,” he said in an interview on the sidelines of the conference.

Holen acknowledged that Moderna has “many new oncology programs [and] not as many” new infectious disease programs, adding that most of the company’s upcoming investigational new drug applications will be in the oncology space.

“I think that makes sense for a couple of reasons,” he explained to Fierce. “One: as you mentioned, the climate; but two: there’s only so many infectious disease vaccines that are relevant, whereas there’s still a huge unmet need in cancer.”

“So if we show activity in cancer, we’ve got lung cancer, prostate cancer, multiple myeloma, melanoma—I mean, a ton of different cancers that we can go after,” Holen concluded.

Related

It’s in melanoma where Moderna has another story to tell at ESMO. The company shared some phase 1/2 data from 29 patients who received two doses of mRNA-4359 in combination with Merck & Co.’s Keytruda. The data demonstrated an objective response rate of 24% in evaluable patients who received mRNA-4359 intramuscularly every three weeks for up to nine doses.

When it came to the nine evaluable patients with PD-L1-positive tumors, Moderna saw responses among six of them, Holen pointed out. Based on these “really compelling data,” Moderna has seen enough to expand development of mRNA-4359 into lung cancer, he said.

While various companies have identified IDO as a target that could complement PD-1/L1 drugs, Holen explained that mRNA-4359 “uses a different mechanism” to target both antigens.

“That mechanism both helps with immune evasion by suppressing [regulatory T cells], but it also can act as a flag where T-cells can then find the cancer and attack the cancer cells directly,” he said.

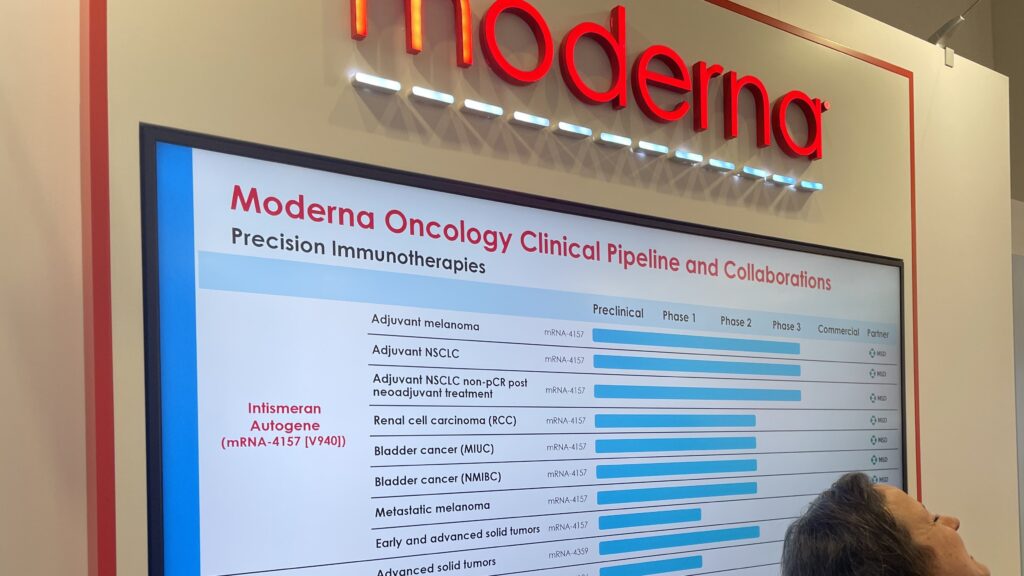

Moderna’s oncology pipeline also includes a Merck-partnered personalized cancer vaccine called intismeran autogene or mRNA-4157. After the FDA pushed back on Moderna’s attempt to seek accelerated approval for the candidate, the company has retooled its approach.

While the Big Biotech had originally been exploring intismeran autogene’s use as an adjuvant, the biopharma recently launched a phase 3 trial of the candidate in metastatic melanoma.

“In fact, ‘4359 showing efficacy in metastatic disease gave us confidence that ‘4157 may actually have a similar efficacy,” Holen said.