Why some memories persist while others vanish has fascinated scientists for more than a century. A preclinical study by Stowers Institute scientists has now identified the mechanism that makes a fleeting moment unforgettable.

The team’s newly reported research, focused on a family of J-domain protein (JDP) chaperone proteins in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, culminates more than 20 years of work, and offers the first direct evidence that the nervous system can deliberately form amyloids to help turn sensory experiences into lasting memories. The results may force a rethink on long-standing assumptions about memory and the consequence of amyloid formation in the brain, potentially providing new avenues for treating amyloid-related disorders of the nervous system.

“I wanted to understand how unstable proteins help create stable memories,” said research lead Kausik Si, PhD, who is Stowers Institute scientific director. “And now, we have definitive evidence that there are processes within the nervous system that can take a protein and make it form an amyloid at a very specific time, in a specific place, and in response to a specific experience.”

“Discovering this chaperone protein has now provided us with an avenue to potentially approach amyloid-based diseases in an unanticipated way,” Si said. “It may be possible to either activate these chaperones and guide toxic amyloids to be less harmful—or, by activating them, we can potentially endow the brain with enhanced capacity to form functional amyloids. This could then override the intrusion of disease-causing amyloids.”

Si and colleagues reported their results of their study in PNAS, in a paper titled “J-domain protein enhances memory by promoting physiological amyloid formation in Drosophila,” in which they concluded, “We posit that the brain harbors chaperones that influence memory by regulating physiological amyloid formation … The relationship between J-domain chaperones and amyloid formation in the context of memory provides a unique perspective on both chaperone function and the role of amyloids in the brain.”

The prevailing model of memory hypothesizes that a change in synaptic strength is one of the mechanisms through which information is encoded in neuronal circuits, the authors suggested. “While changes in synaptic strength require alterations in the synaptic proteome, the mechanisms that initiate and maintain these changes in synaptic proteins remain unclear.”

Molecular chaperones play a critical role in proteome function, and act as an interface between the environment and the proteome, the team continued. “Beyond their well-defined role in maintaining proteome integrity, chaperones perform a multitude of other functions, including de novo protein folding, assembly and disassembly of protein complexes, and regulation of protein translocation and activity.”

Chaperones guide proteins to attain the correct folded state. It has long been thought that in the nervous system, chaperones help proteins to either fold correctly or prevent proteins from harmful misfolding and clumping. The study by Si and colleagues found that in Drosophila, one of a family of J-domain protein chaperones, CG10375, which they named “Funes”, does something unexpected—it allows proteins to change their shape and form functional amyloids that house long-term memory.

“This expands the idea of a protein’s capacity to do meaningful things, and suggests there is an unknown universe of chaperone biology that we’ve long been missing,” Si said.

Amyloids are typically associated with neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s and Parkinson’s. They form tightly packed, highly stable “detrimental” protein fibers that destroy brain cells, erasing the memories of their host.

The new research supports the Si Lab’s 2020 study which explained that amyloids are not always harmful unregulated byproducts as previously thought. The findings reported in PNAS also demonstrate that amyloids can be carefully controlled—serving as tools the brain uses to store information. Ultimately, the research reveals for the first time a critical step in the process of how long-lasting memories endure.

The Si Lab knew from their 2020 study, which was led by former Stowers postdoctoral research associate Rubén Hervas, PhD, now an assistant investigator at the University of Hong Kong, and co-corresponding author on the newly reported research, that the formation of amyloids can allow animals to form stable memory. “But we did not know how or when,” Si said. “The fact that amyloid is needed to form memory implied there must be a mechanism that controls the process,” Hervas said.

The researchers hoped that if they could identify the mechanism, they could also manipulate it in a meaningful manner to influence memory. “Despite 100 years of studying amyloid biology, nobody has ever asked how the brain can deploy amyloid,” Si explained. “Because amyloid formation was historically thought to be unintentional and unintended, it was now necessary for us to ask that question.”

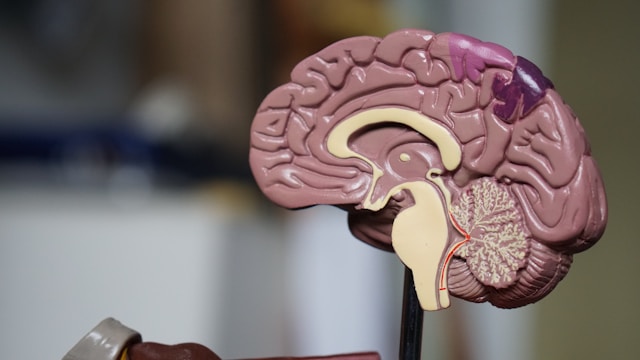

In 2003, Si first discovered the existence of a functional amyloid in the sea slug. With just 10,000 neurons, this simplified system was a first but pivotal step toward rethinking amyloid biology. His lab then expanded the research to more complex animals including fruit flies (~150,000 neurons), mice (70-80 million neurons), and even humans (~86 billion neurons). The team eventually uncovered that an amyloid-based mechanism is broadly used for memory persistence.

In fruit flies, a prion-like protein called Orb2 (and its relative protein CPEB in mammals) must undergo self-assembly at the synapses, the gap between two neurons, to maintain a memory. “Orb2 belongs to a class of nonpathological amyloids, where amyloid formation enables a protein to acquire a new function,” they noted in the PNAS paper. Over time, the researchers began to hypothesize that the difference between a harmful and a helpful amyloid may depend on whether Orb2’s assembly process is tightly regulated by other proteins.

Through their newly reported study the team was able to test that hypothesis. To find the regulator, they investigated a family of chaperones that manage protein behavior in neurons and, using an associative memory model, they identified a previously uncharacterized chaperone.

“We were inspired by Jorge Luis Borges’ short story ‘Funes the Memorious’ in which one man’s perfect memory comes at a cost, so we named the chaperone Funes,” said Kyle Patton, PhD, a former Stowers Graduate School student and lead author on the study.

The researchers discovered Funes by manipulating the concentrations of 30 different chaperones in the fly’s memory centers. “We trained very hungry fruit flies to link a specific, unpleasant smell with a sugar reward,” Patton said. Flies with increased levels of Funes showed a remarkable ability to remember the odor-reward link after 24 hours—a standard proxy for long-term memory.

But the most surprising discovery came at the molecular level. At his lab in Hong Kong, Hervas engineered Funes variants that could bind Orb2 but could not trigger its transition into amyloid and found the flies’ long-term memory failed. This indicated that Funes is an essential component for long-term memory formation.

“Here, we report the identification and characterization of a type III JDP, CG10375, (henceforth referred to as Funes) from Drosophila melanogaster, which positively affects memory when overexpressed in specific neuronal populations,” the team summarized. “The identification of the type III JDP Funes reveals an unanticipated function of molecular chaperones: the promotion of functional amyloid formation in the brain to help encode memory … Mechanistically, Funes promotes the formation of the translationally active amyloid of Orb2, an mRNA-form binding protein that is essential for long-term memory.”

Si suggested, “We are now getting early evidence that, like the fruit fly shows in this study, the process may also be manifesting in the vertebrate nervous system. Our hypothesis is carrying us all the way to the vertebrate brain, illustrating that it may actually be universal.”

While screening the chaperone proteins in fruit flies, the team made another unexpected connection that potentially broadens the study’s relevance. Funes was the most striking, but not the only chaperone to affect memory. “Curiously, some of the memory-modulating Type III JDPs identified in this work have been linked to schizophrenia, a condition with symptoms that include deficits of episodic memory,” the authors stated. “If you look at the human version of these genes, they have surprisingly been implicated by genome-wide association studies in schizophrenia,” Patton said. “That’s not something we anticipated.”

Patton cautioned that the overlap does not mean schizophrenia is a “disease of chaperones,” but it opens the door to the possibility that the chaperones could be key factors, potentially acting as mediators. “At this stage, the mammalian functional orthologue of Funes is unknown,” the researchers further noted. “The identity and function of mammalian orthologue of Funes would be of considerable interest.”

“Ultimately, chaperones may allow the brain to perceive, process, or store information about the outside world,” Si said. “And in diseases where we do not see the world as it is, like schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, we could imagine chaperones playing a role.”

“While it’s an unknown universe, it’s an exciting one, and we’ll see where we end up,” Si added. “What’s remarkable is that we’re now thinking about new ways to treat human diseases, and it all started by studying the sea slug, an organism that, compared to us, is relatively simple.”