A team of scientists at the Institute for Cell Biology (Cancer Research), University of Duisburg-Essen, has developed a simple method for the automated manufacture of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived lung organoids (iPSC-LuOrgs) in a stirred-tank bioreactor equipped with a membrane stirrer. The organoids, formed as miniature structures containing populations of lung cells, could potentially be used to test early-stage experimental drugs more effectively, without the use of animal material. The researchers, headed by Diana Klein, PhD, suggest the new production technology could revolutionize the development of treatments for lung disease. In the future, they suggest, it may even be possible to grow personalized organoids from a patient’s own tissue to test potential treatments in advance.

“The best result for now—quite simply—is that it works,” said Klein, who is first author of the team’s published paper in Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology. “This means that, in principle, lung organoids can be produced using an automated process. These complex structures represent the in vivo situation better than conventional cell lines and thus serve as an excellent disease model … In the next step, the organoids could also be used to test potential therapeutics using high-throughput methods. Which ones are effective and at what concentration? This could accelerate the development of specific medications for patients. Furthermore, the organoids could also be used to predict patient-specific reactions to radiotherapy or other potential treatments.”

Klein and colleagues reported on their technology in a paper titled “Upscaling: Efficient generation of human lung organoids from induced pluripotent stem cells using a stirring bioreactor,” in which they concluded, “These freely floating LuOrgs are now available in large numbers for the investigation of, for example, cancer therapy approaches as a new and patient-oriented in vitro platform.”

The lungs are responsible for the basic function of breathing, the authors noted, “… so any damage to the lungs caused by pulmonary diseases can significantly affect the life expectancy and overall quality of life.” Finding better treatments for lung diseases would save millions of lives worldwide. “The gradual increase in the number of serious lung diseases, as highlighted by the recent global pandemic resulting from the SARS-CoV-2 virus in 2019 (COVID-19), has increased awareness regarding research on respiratory diseases and sparked interest in the development of suitable human lung mimetics to better understand as well as therapeutically address such pathological events in a patient-centric manner,” the team continued.

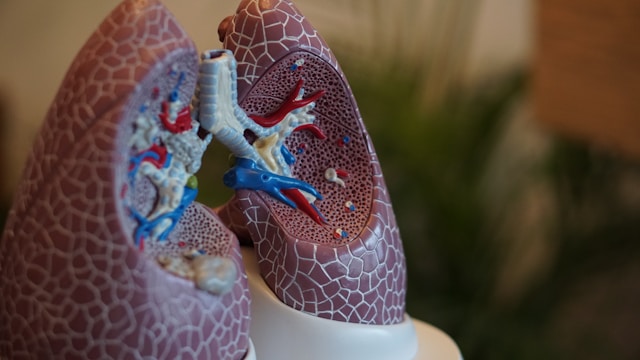

However, lungs are a complex structure, and difficult to model in the lab. “The complex three-dimensional architecture of the human lung, with its numerous hollow interconnected airways, alveolar units, and pulmonary capillaries, presents particular challenges in tissue engineering for lung (re)generation.” Lung organoids are a promising option for research, the team continued. However, until now, they’ve required too much painstaking manual work for them to be used in preclinical medical testing.

The team recently established what they described as “… a very simple and practical protocol for producing iPSC-derived lung organoids in ultra-low attachment plates and without relying on a gel-like extracellular matrix.”

Klein explained, “You take a starting cell, in our case the stem cell, and multiply it—the cells grow in a suitable plastic dish. Once the cells have grown sufficiently, you then detach them from the plastic dish and ‘animate’ the cells to form small cellular aggregates. We do this by placing a certain number of cells in an anti-adhesive dish. The cells then float together and form embryoid bodies. These structures are treated with various growth factors, substances that are typically found in the lungs or during lung development. In the presence of these substances, the cells transform into various cell types that are found in the lungs.”

For their newly reported study, the scientists modified their protocol to a bioreactor setup. They put the embryoid bodies into a bioreactor tank with a continuously stirring membrane, which contained a suitable medium for growing the organoids. “In this work, we adapted this protocol for use in a unique membrane-stirred tank bioreactor to enable large-scale differentiation of predifferentiated embryoid bodies derived from iPSCs into LuOrgs,” they wrote. “Unlike similar stirred-tank bioreactors, our system is equipped with a special membrane module for gassing.” The researchers also manually cultured a control set of organoids on a conventional growth plate.

The organoids spent four weeks in the bioreactor and were then analyzed using microscopy, immunofluorescence, immunohistochemistry, and RNA sequencing to see how the organoids had developed, what cells had formed, and how comparable they were to conventionally grown organoids.

Their analyses confirmed that both sets of organoids had developed the lung-like structures representing airways and alveoli that scientists were looking for. RNA sequencing showed that they had developed characteristic epithelial and mesodermal lung cells. Both sets developed the same types of cells, although in slightly different proportions—for example, manually generated lung organoids contained more alveolar cells. The organoids developed in the bioreactor seemed to be larger, with fewer alveolar spheres.

The fact that the bioreactor technology can produce more organoids at a time, with less manual work, could be a game-changer for lung disease research. “As a more ethical alternative to animal models, (spheroidal) LuOrgs as miniature 3D lung structures offer a higher degree of tissue complexity and heterogeneity, representing a faster and more viable method for accurately simulating and ultimately modulating human lung physiology,” the researchers stated. However, they acknowledge that more testing will be needed to establish the best conditions for organoid development, and the organoids themselves will need to be improved to mimic real-life conditions within the body better.

“Organoids can’t yet fully recapitulate the lung cellular composition,” said Klein. “Some cells are still missing for the ‘big picture,’ such as infiltrating immune cells and blood vessels. But the organoids themselves show very good bronchiolar and alveolar structures! We obviously don’t have blood flow, meaning the conditions are rather static. But for a patient-oriented screening platform, this may not be necessary, if important insights into the cells’ fate during a certain treatment can be obtained. These systems may not yet be as complex as an entire organism, but they are human-based—we have the cells that we also find in patients.”

Klein added, “There is still a lot of room for optimization. We need robust and scalable protocols for large-scale organoid production. This requires careful consideration of the bioreactor design, the cell types to be used, and the conditions under which the organoids are cultivated. But we’re working on it!”

In their paper, the authors further commented, “Further efforts by our research group focus on complete differentiation in the bioreactor, i.e., proliferation of iPSCs and subsequent initiation of differentiation directly in the bioreactor culture vessel, which would further simplify and accelerate the process.”