From a blood test, scientists may be able to predict when a person is likely to develop symptoms of cognitive impairment associated with Alzheimer’s disease. That is according to data from a new study led by a team from the Washington University School of Medicine and their collaborators. The work is published in a new Nature Medicine paper titled “Predicting onset of symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease with plasma p-tau217 clocks.” In it, the scientists describe developing clock models that predicted the onset of Alzheimer’s symptoms within a margin of error of three to four years.

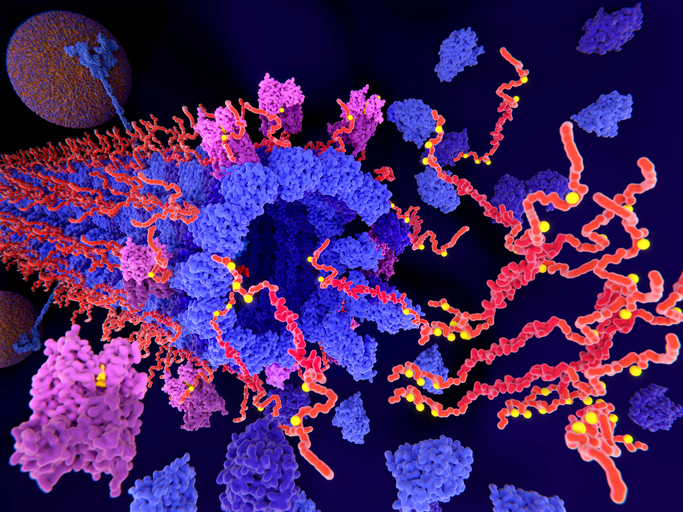

The models rely on the presence of the p-tau217 protein in plasma samples to estimate the age when the person in question is likely to begin experiencing Alzheimer’s symptoms. Previous studies have shown that plasma p-tau217 correlates strongly with amyloid and tau build up in the brain based on PET scans. Doctors can use the levels of the protein in plasma to diagnose Alzheimer’s in patients with cognitive impairment. However, these tests are not currently recommended in individuals who are not cognitively impaired outside of clinical trials or research.

To identify the interval between elevated p-tau217 levels and symptom onset, the team analyzed data from volunteer participants in two independent Alzheimer’s research initiatives: the WashU Medicine Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center and the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. The participants included over 600 older adults. Plasma p-tau217 levels across both cohorts were measured using several blood tests including PrecivityAD2, a diagnostic test from C2N Diagnostics, a WashU startup.

“Amyloid and tau levels are similar to tree rings—if we know how many rings a tree has, we know how many years old it is,” said Kellen Petersen, PhD, lead author on the study and an instructor in neurology at WashU Medicine. “It turns out that amyloid and tau also accumulate in a consistent pattern and the age they become positive strongly predicts when someone is going to develop Alzheimer’s symptoms. We found this is also true of plasma p-tau217, which reflects both amyloid and tau levels.”

The data showed that older individuals had a shorter time from when elevated p-tau217 appeared until they started experiencing symptoms compared to younger participants. It suggests that younger people’s brains may be more resilient to neurodegeneration and that older people may develop symptoms at lower levels of Alzheimer’s pathology. For example, if a person had elevated p-tau217 in their plasma at age 60, they developed symptoms 20 years later. If p-tau217 wasn’t elevated until age 80, they developed symptoms only 11 years later. Their analysis also showed that this predictive approach works with multiple p-tau217-based diagnostic tests besides PrecivityAD2.

The findings reported in this study could have important implications for clinical trials that are testing preventive Alzheimer’s treatments as well as for identifying individuals that are likely to benefit from these therapies. According to at least one estimate, more than seven million Americans live with Alzheimer’s disease with health and long-term care costs for this and other forms of dementia projected to reach nearly $400 billion in 2025. Predictive models like the one described in the Nature Medicine paper could be crucial for both developing and testing treatments.

“Our work shows the feasibility of using blood tests, which are substantially cheaper and more accessible than brain imaging scans or spinal fluid tests, for predicting the onset of Alzheimer’s symptoms,” said Suzanne Schindler, MD, PhD, senior author on the paper and an associate professor in the WashU Medicine department of neurology. “In the near term, these models will accelerate our research and clinical trials” but “eventually, the goal is to be able to tell individual patients when they are likely to develop symptoms, which will help them and their doctors to develop a plan to prevent or slow symptoms.”

Additionally, “with further refinement, these methodologies have the potential to predict symptom onset accurately enough that we could use it in individual clinical care,” Peterson noted.