Many vaccines work by introducing a protein to the body that resembles part of a virus. Ideally, the immune system will produce long-lasting antibodies recognizing that specific virus, thereby providing protection. Scientists at Scripps Research have now made a new discovery for some HIV vaccines. The scientists discovered that repetitive HIV vaccinations can lead the body to produce antibodies targeting the immune complexes already bound to the virus.

Their finding is published in Science Immunology in an article titled, “Anti-Immune Complex Antibodies are Elicited During Repeated Immunization with HIV Env Immunogens,” and could lead to better vaccines.

“These anti-immune complex antibodies have not been studied in very much depth, especially in the context of HIV vaccination,” said Andrew Ward, PhD, professor of integrative structural and computational biology at Scripps Research and senior author of the new paper. “Understanding these responses could lead to smarter vaccine designs and immunotherapeutics. It’s an exciting step forward in fine-tuning antibody and vaccine-based strategies against HIV and other diseases.”

The new observation came about when Ward’s team was using advanced imaging tools to study how antibodies evolve after multiple HIV vaccine doses.

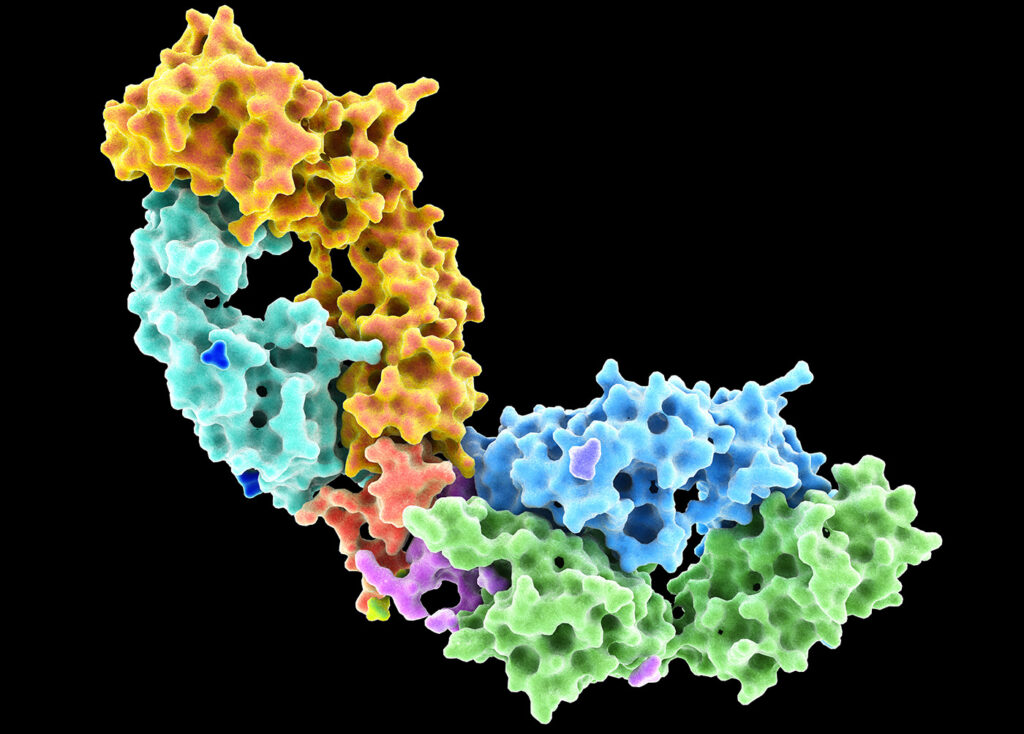

A technique invented by the lab, known as Electron Microscopy-Based Polyclonal Epitope Mapping (EMPEM), lets the researchers see exactly where on the HIV virus antibodies bind. When they carried out the experiments on blood from animals that had received multiple doses of an experimental HIV vaccine, they discovered some of the antibodies were not binding directly to the HIV viral antigen, but to immune molecules on its surface.

“These antibodies actually make no direct contact with the viral protein,” said Sharidan Brown, a graduate student at Scripps Research and first author of the new paper. “We are the first to structurally characterize this kind of antibody in the context of HIV vaccination.”

Scientists have previously known that anti-immune complex antibodies could form in some situations. This happens when the immune system recognizes antibodies already bound to viral proteins. An additional immune response occurs, spurring the production of new antibodies, including some that bind to existing immune complexes on the virus’ surface.

In a series of follow-up experiments on HIV-vaccinated animals, Brown, Ward, and their colleagues showed that these kinds of anti-immune complex antibodies often emerge between the second and third administrations of a vaccine.

“We showed that these antibodies exist but what we don’t yet know is how they shape the immune response,” explained Brown. “They could be detrimental because they are not directly neutralizing the virus, but they could lead to larger immune complexes which actually spur more activity against the viruses and infected cells in ways that we don’t fully understand.”

If future experiments show that the antibodies are unwanted, it could guide vaccine design strategies to minimize the immune complex response and improve the ability for vaccines to directly neutralize HIV.

“Minor changes between each dose could create just enough diversity that you don’t produce antibodies against antibodies,” said Brown.

Looking toward the future, the research team is planning to continue studying the antibodies, as well as whether similar antibody responses are produced after multiple doses of other vaccines or during natural infection.