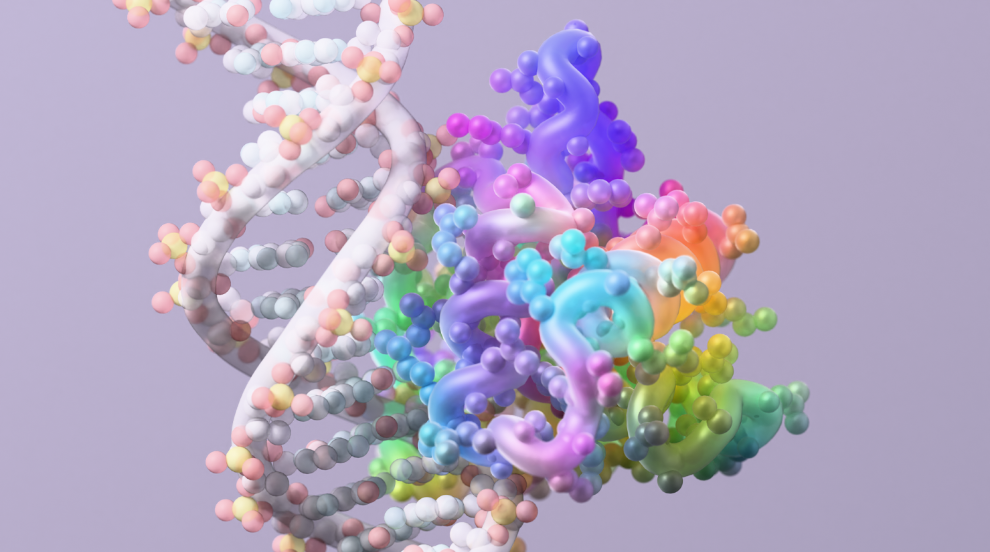

Researchers from the lab of Nobel laureate, David Baker, PhD, have now released RFdiffusion3 open source. The latest version of the de novo protein design model generates proteins that interact with any type of molecule, including DNA and small molecules with broad applications across sustainability and therapeutics.

“We built this as a general model and are sharing it freely so the scientific community can create things we haven’t even imagined yet,” said Rohith Krishna, PhD, postdoctoral researcher in the Baker lab and co-lead author of the RFdiffusion3 bioRxiv preprint that has not been peer reviewed.

The work shows experimental proof of concept for the design of proteins that recognize specific sequences of DNA, which serves as a foundation for synthetic transcription factors for gene therapy, and complex enzyme catalysis, which offers industry applications.

Baker, who is the director of the Institute for Protein Design at the University of Washington (UW) and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) investigator, won the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the design of novel proteins. RFdiffusion3 is one step closer to designing and understanding biological complexity, a challenge Baker recently described to GEN as one of the main obstacles to overcome for de novo design to transform medicine.

RFdiffusion3 enters a growing ecosystem of protein design models that cover multiple modalities, such as BoltzGen, which was released in October. BoltzGen demonstrated generalizable therapeutic design in any format, including nanobodies, mini-binders, and disulfide-bonded peptides, and against any target across nucleic acids, small molecules, and both ordered and disordered proteins. Notably, BoltzGen designs binders only and does not generate catalytic enzymes as demonstrated by RFdiffusion 3.

To achieve intricate chemical interactions with new precision, RFdiffusion3 treats individual atoms as the fundamental units being designed, a methodological advance from its predecessor, RFdiffusion2, concurrently published in Nature Methods, which implements a hybrid atom and amino acid residue approach. In computational time, RFdiffusion3 exhibits ten-fold faster performance over RFdiffusion2, despite taking a more computationally intensive all-atom method.

Krishna told GEN that the underlying intuition for RFdiffusion 3 was to give “more knobs for generality and controllability.” As an example, the model’s all-atom approach can allow the specification of a hydrogen bond to a particular atom, a level of precision that can greatly facilitate the construction complex reactions, such as enzyme catalysis. He also notes that RFdiffusion3 has limitations when designing against biomolecules not seen in the training set, such as non-canonical amino acids.

Straight from the computer

While RFdiffusion3’s open-source launch opens the door for a new wave of enzyme innovation across the community, the Baker lab is already charting an impressive path forward in complex catalytic design.

In a concurrently published Nature paper, the UW researchers applied RFdiffusion2 to demonstrate the successful design of metallohydrolases, enzymes that cleave some of the most difficult bonds in biology, such as protein peptide bonds, by leveraging the reactivity of a metal. Metallohydrolases have been of particular interest for degrading difficult pollutants.

As successful de novo enzyme design builds protein structures that contain an ideal active site of catalytic residues that stabilize the transition states of a reaction, RFdiffusion2 made the advance of eliminating the need to specify sequence position and backbone coordinates for each catalytic residue to expand the sampled space.

“Rather than borrowing constraints from nature, we found that giving the model more freedom can lead to creative solutions and higher the success rates for these enzyme design problems,” explained Woody Ahern, graduate student in the Baker lab and co-lead author of the Nature paper in an interview with GEN.

Out of thousands of computational metallohydrolases designs, the authors experimentally screened 96 enzymes for the hydrolysis of the target molecule. Notably, five out of 96 designs showed proficient hydrolysis activity. One design, named ZETA_1, demonstrated high catalytic efficiency several orders of magnitude higher compared to previously designed metallohydrolases.

Seth Woodbury, another graduate student in the Baker lab and co-lead author, highlighted that achieving this success rate from a small batch without starting from a natural enzyme represents a major step forward in enzyme design. Optimized catalysts can be produced on the first attempt with minimal catalytic information, straight from the computer, and lead to effective wet lab use.

“This establishes a general and reproducible route for creating new biocatalysts from scratch, opening the door to rapidly designing potent enzymes for virtually any reaction,” Woodbury told GEN.

Donghyo Kim, PhD, postdoctoral researcher in the Baker lab and another co-lead author of the metallohydrolases study, adds that one interesting feature of de novo designed enzymes is their improved thermostability, which is valuable for catalytic reactions that can occur more efficiently at higher temperatures. “Enzyme stability is a great property for industrial use, such as degrading plastics,” said Kim.

The field looks forward to the next generation of complex proteins designed by RFdiffusion3.