A retinal implant developed by Science Corp. has for the first time restored some functional vision to patients with a severe form of age-related macular degeneration (AMD), a common eye disease and the leading cause of blindness in older adults, according to a new study.

The study, published Oct. 20 in The New England Journal of Medicine, is promising news for the California-based medtech company and the more than 5 million people around the world who suffer from AMD.

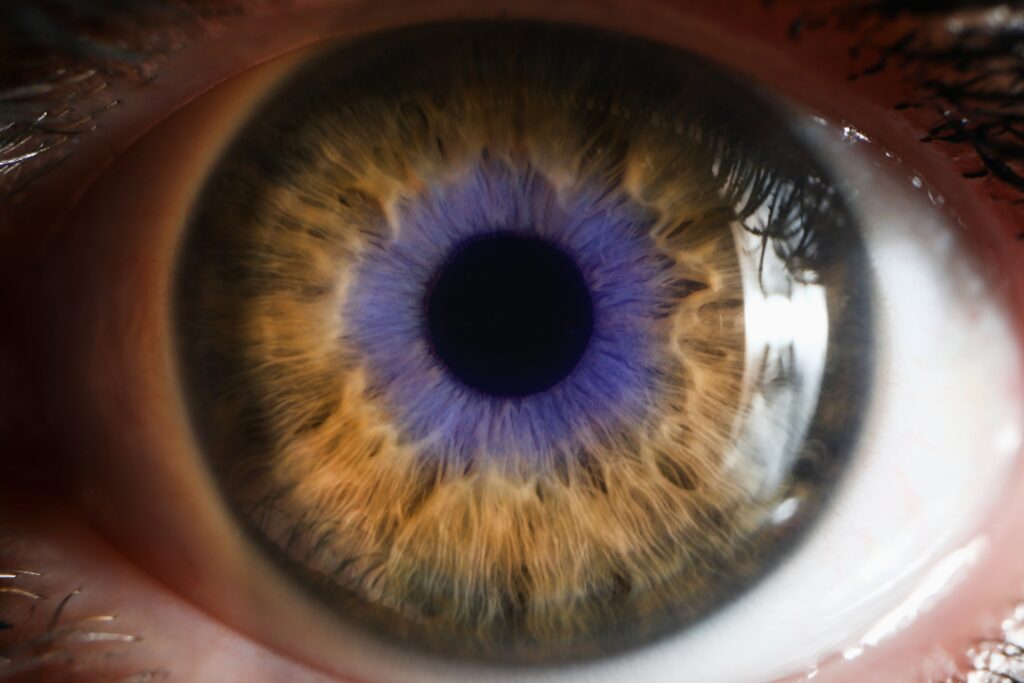

The study evaluated the efficacy of Science’s PRIMA brain-computer interface retinal implant in patients with geographic atrophy, an advanced form of AMD that results in the loss of retinal cells, causing blurriness and blind spots in a person’s central vision. Most people diagnosed are over 60.

Of the 32 patients who received the implant as part of a clinical trial, 27 had enough improvement in their vision after a year to read letters, numbers and words, according to the study. Meanwhile, 26 experienced significant improvement in visual acuity. On average, the patients posted a gain of more than five lines on a standard eye chart.

Nineteen patients experienced side effects, including high pressure in the eye, retinal tears and bleeding, but the study’s authors said most of these resolved within two months.

The trial marks “the first time that an attempt at vision restoration in these cases has achieved results – and in such a large number of patients,” José-Alain Sahel, M.D., a co-author of the study, said in an announcement.

Sahel, a professor of ophthalmology at the University of Pittsburgh and Sorbonne University in Paris, said some of the patients are reading pages in a book, “something we couldn’t have dreamt of” a decade ago.

Frank Holz, M.D., lead author of the study and chair of the ophthalmology department at the University of Bonn, described the implant as “a paradigm shift in treating late-stage AMD,” because it actively restores lost vision. Current therapies for AMD only slow progression of the disease.

The PRIMA system, based on research by Stanford University professor of ophthalmology Daniel Palanker, Ph.D., pairs a tiny wireless chip about the size of a pinhead with special glasses equipped with a camera.

The glasses project near-infrared light to the implant, which acts as a miniature solar panel, according to the company. The implant is placed in the retina and replaces photoreceptors lost because of the disease, stimulating the remaining cells to carry the visual signal to the brain. The system also includes a “zoom-in” feature allowing patients to magnify letters.

The device provides only black-and-white vision, and, for now, the resolution is relatively low, Palanker said in an article on Stanford Medicine’s website. But Science said it is already working on the next version of the device, “which will optimize visual performance further with digital image processing and streamlined ergonomics to bring this technology to more patients.”

The company has filed for regulatory approval in Europe and is also pursuing approval from the FDA. It said it hopes to begin selling the device to patients in Europe by next year.